Making-Of

Get an insight behind the scenes and watch more footage! Discover the different research formats such as the workshop and details of the questionnaire. Find out more about the work on the ground, Jordan’s people and their great hospitality.

Summary

The “Double Shift” research project explores the impact of the Syrian conflict on the Jordanian education system. Since 2011, the Kingdom of Jordan has seen a massive influx of refugee children from Syria. Various structural approaches have been introduced throughout the country to enable the integration of Syrian school children into the Jordanian education system. The project focuses on the double-shift system, by which Jordanian children attend school in the mornings and Syrian children in the afternoons. During field trips to Jordan, the participating researchers and designers used qualitative approaches involving artistic and social science methods to collect data and generate visual material.

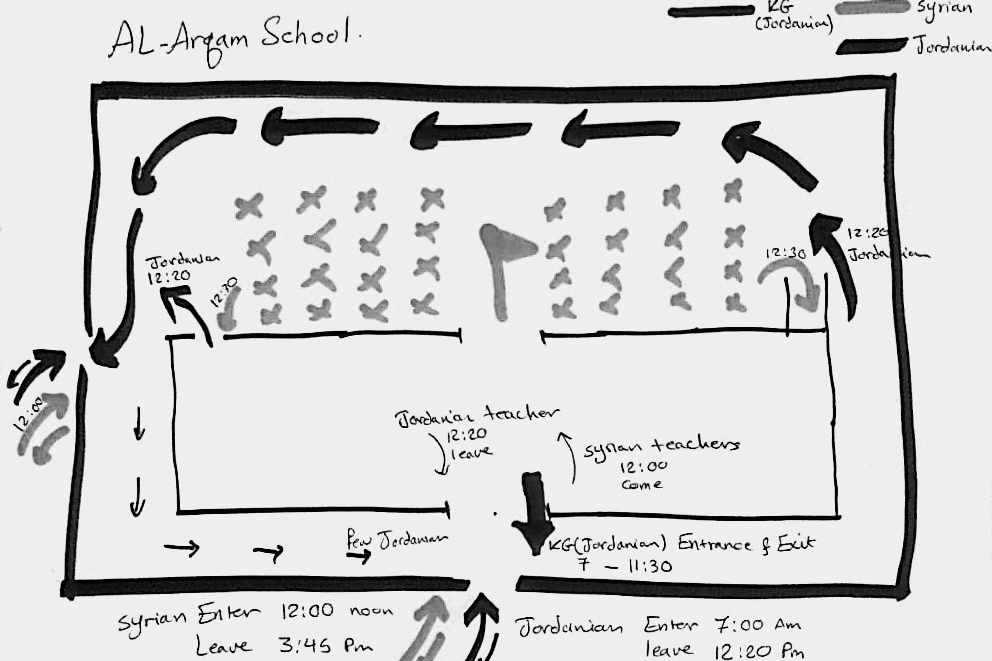

One object of investigation is the double-shift school Al-Arqam in the industrial city of Sahab, southwest of Amman, Jordan’s capital. A questionnaire was used to learn more about the school’s situation and students’ needs. A participatory workshop produced insights about students’ daily routines, and various stakeholders (headmaster, UNICEF, etc.) were interviewed to report on the current situation in Jordan, describe their personal impressions, and name their wishes for the future.

Project background – Visual Society Program

“Double Shift” emerged as part of the Visual Society Program (ViSoP). The program is a collaboration between the Berlin Social Science Center (WZB) and the “Visual Systems Studio Class” at Berlin University of the Arts (UdK), enabling scientists and designers to work together in teams and develop an understanding of the basic principles, methods, and techniques of each other’s disciplines. It was initiated by David Skopec, full professor for “Visual Systems Studio Class” at UdK. The project was continued and finalized at WZB.

In the program, designers collaborate with social scientists to cross the boundaries of their respective disciplines. The goal is to create new perspectives on topics relevant to society, and to visualize social science research findings in an analytically sound manner. The program is designed to help promote interdisciplinary work and research and to stimulate a critical assessment of conventional methods. Designers and social scientists can develop new forms to disseminate social science findings to a wider audience, and they can try out new tools and methods to approach research issues for which traditional social science methods are insufficient. Given the increasing complexity of societal and scientific questions, the program attempts to train designers and social scientists to become “transformers” capable of disseminating research knowledge into society.

Jordan

Jordan is a relatively-small, almost-landlocked country with a population numbering at 9 million. The dominant religion in Jordan is Islam, which is practiced by around 92% of the population. It coexists with an indigenous Christian minority. Jordan is considered to be among the safest of Arab countries in the Middle East. The Kingdom has been giving shelter to refugees since its foundation in 1946, as now to many Syrians escaping their home country.

Consequently, Jordan is rich in culture, tradition and food. Jordan’s national dish is Mansaf. It is a symbol for Jordanian hospitality and is influenced by the Bedouin culture. Mansaf is eaten on different occasions such as weddings or religious holidays and also at funerals. It consists of lamb boiled in thick yogurt and is served with rice or bulgur sprinkled with nuts on a large bedouin style platter. As Jordan is the 8th largest producer of olives in the world, olive oil is the main cooking oil in Jordan.

Amman

Situated in north-central Jordan, the capital Amman is the country’s economic, political and cultural centre. The city’s population has more than doubled since 2004. Over 4 million people live in Amman. The city is considered to be among the most liberal and westernized Arab cities. The Worldwide Cost of Living Report 2017 ranked the capital as the most expensive Arab city to live in. It is a major tourist destination in the region, particularly among Arab and European tourists.

Amman was initially built on seven hills but now spans over 19 hills combining 27 districts. The Areas have either gained their names from the hills (Jabal) or valleys (Wadi) they are situated on, such as Jabal Weibdeh and Wadi Abdoun. East Amman is predominantly filled with historic sites that frequently host cultural activities, while West Amman is more modern and the economic center of the city. Most of the Syrian refugees are living in East Amman. The public transportation network of Amman is not expanded and not well signposted. For those who cannot afford a car or a taxi, it’s quite challenging to get around the city. The Jordanian design agency Syntax helped addressing this issue by designing Amman’s first public transportation map.

School visits

On the first field trip to Amman the entire project team was on board. The goal was to get an overview of the local situation. To that end, two schools were visited and meetings with several stakeholders, including UNICEF, USAID, EBRD, and Consolidated Consultants Group took place. Those conversations helped the team to learn about Jordan’s situation from different perspectives and to identify the challenges that individuals and, first and foremost, the country of Jordan are confronted with. The Madrasati Initiative made it possible for the team to visit two schools.

The Jordanian school week starts on Sunday and ends on Thursday, Friday and Saturday are off. In addition to public schools there are private, UNRWA and Armed Forces Culture schools. The project team visited two public schools. The first school was an all-boys school in the north of Jordan, located in the small village of Som in the Irbid region. This was a single-shift school. The second school was a double-shift school in Sahab, an industrial city southeast of Amman, Jordan’s capital. In both schools, the team experienced a warm and open welcome. In conversations with the headmasters, the team learned a lot about each school’s situation. In addition, personal tour around the school were offered.

Single-shift school in Som

“The single-shift school is an all-boys school and was built in 1948 by the Som community in the Irbid region. The school enrols 630 students, of which 130 are Syrian refugees. Jordanian and Syrian boys share the same classroom. Even though the classrooms are no larger than 23 square meter, they have to accommodate between 25 and 40 children. The school suffers from a lack of teachers and resources. Activities can only take place outside because there aren’t enough rooms. In the winter, it is very cold inside the school; in the summer, it is hot and muggy. In the small classrooms, there is a lack of oxygen. The headmaster, Shaman Ma’abrah, offers us a warm welcome and some tea and biscuits. He doesn’t speak English. Tala Sweis translates what he is saying. He tells us about the school’s situation and the improvements he would like to see at his school. His wish list includes an additional water tank, more teachers, more rooms, and a fence to keep the neighbors’ goats from entering the school yard. We are given a tour of the school and visit a group of first graders, who welcome us in English. We look at the chemistry lab and the carpentry workshop in which students create new pieces of furniture from old ones. Som is home to 400 Syrian families. 130 children could already be admitted to the school; another 200 still have to be accommodated. The headmaster is not a big fan of the double-shift system, but he thinks of introducing it in the future, saying this is the only way to provide more children with a formal education.”

Marjam and Paula // Designers, team members of “Double Shift”

Impressions of the school visit

Double-shift school in Sahab

“We visited the Al-Arqam school on a Saturday. On Saturdays, the school hosts the remedial center, a tutoring program organized by Madrasati. It provides Jordanian and Syrian children, who are otherwise separated by shift, with a place to meet. Using playful methods, they study English, mathematics, reading, writing, or the hours of the day together. The mood is cheerful and lively. The teachers here do their job with an unbelievable calmness and energy at the same time. It’s easy to see that the children are having fun. The school offers additional activities to foster integration, including a soccer club. In the beginning, headmaster Sawsan Abu Hammad reports, there was a gap between the Jordanian and the Syrian children. That gap could be closed by the remedial center and by shared activities. Again, we ask the headmaster about the improvements she would like to see at her school. She says she wishes the school had an awning for the school yard to protect the children from the mid-day sun while waiting for their shift to start. As a second wish, she mentions a decent heating system. Last but not least, she wishes the school had more tables, because the double shift model also places a double strain on tables and benches, causing them to break more quickly.”

Marjam and Paula // Designers, team members of “Double Shift”

Calculation “Benefits through education”

“We want to caption the benefits of education not just to the children but also to Jordan as a whole. Education benefits the society in many ways of which some are quantifiable while others are not. One aspect that can be put in numbers is the additional wage that adults earn due to their better education. We compare this gain with the costs for school material and personnel to establish that educating as many out-of-children is worthwhile financially - on top of all the other advantages.

Method

From the ministry of education’s plans we can infer the costs of educating out-of-school children. This includes money for teachers’ and admins’ salaries, textbooks, operational costs (water, electricity, fuel), furniture, and maintenance.

To get to the additional wage earned we have to combine different sources: Based on documents of the Department of Statistics Jordan we estimate lower bounds on wages earned by different educational backgrounds for non-Jordanians in Jordan. Next, we combine this with the share of educational degrees held by non-Jordanians in Jordan who went to school in Jordan. From this we can estimate the wage premium that can be expected from sending out-of-school children to school, taking into account different abilities (educational outcomes). Finally we calculate the present value of the total wage premium using gender specific retirement ages, the share of non-working Syrians in Jordan, an average interest rate over the last 10 years and an exchange rate of 1JOD = 1.4094 USD. Notice that this is a very conservative approach using only the lower bounds on wages for different educational backgrounds, two missed years of school for out-of-school children and uniform out-of-work rates. With this we arrive at a present value of gross benefits of 3,873 USD per out-of-school child.

Finally we estimate number of out-of-school Syrian children in Jordan combining UNICEF’s numbers on age distribution of Syrian children in Jordan with the Ministry of Education’s data on Syrian enrolment rates in the public school system. With this we arrive at a total of 79,452 out-of-school Syrian children in Jordan.”

Philipp // Economist, team member of “Double Shift”

List of inputs/assumptions

Age of starting work

Less than secondary education: 16 years

Secondary education: 18 years

Retirement age

Men: 60 years

Women: 55 years

Discount rate

3.5 percent p.a.

Education levels (of non-native workers

previously enroled in Jordan’s education system)

Literate or basic education

Men: 56.23 percent

Women: 61.81percent

Secondary, vocational or higher

Men: 43.77 percent

Women: 38.19 percent

Missed school years of out-of-school children

2 years

Share of out-of-work syrians in

the working age population

Men: 40.3 percent

Women: 87.4 percent

Lower brackets of average wages of workers

in Jordan for different educational backgrounds

Illiterate

Men: JOD 215.6 per month

Women: JOD 160.7 per month

Less than Secondary

Men: JOD 252 per month

Women: JOD 185.2 per month

Secondary

Men: JOD 276 per month

Women: JOD 234.7 per month

Research at Al-Arqam school

The double-shift school Al-Arqam was the main research object of “Double Shift”. There social science research methods and design research methods were applied to examine the school’s situation and to capture the feelings of individual students.

In addition to traditional survey techniques such as questionnaires and interviews with stakeholders, film documentation, photographic portraits, a participatory workshop, and cultural probes were used to capture personal experiences on the ground. The questionnaire asks respondents about the school’s situation and about students’ individual needs. The film and photo documentary of the shift change serves to capture the school’s daily routines. The workshop helps to learn more about the students’ daily routines. To the same end, the cultural probes technique is used: Nine students, four Jordanian and five Syrian students, from sixth and seventh grade took pictures to document their daily routines and their school life. To document the students’ wishes, portraits of them holding their wishes written on signs were taken.

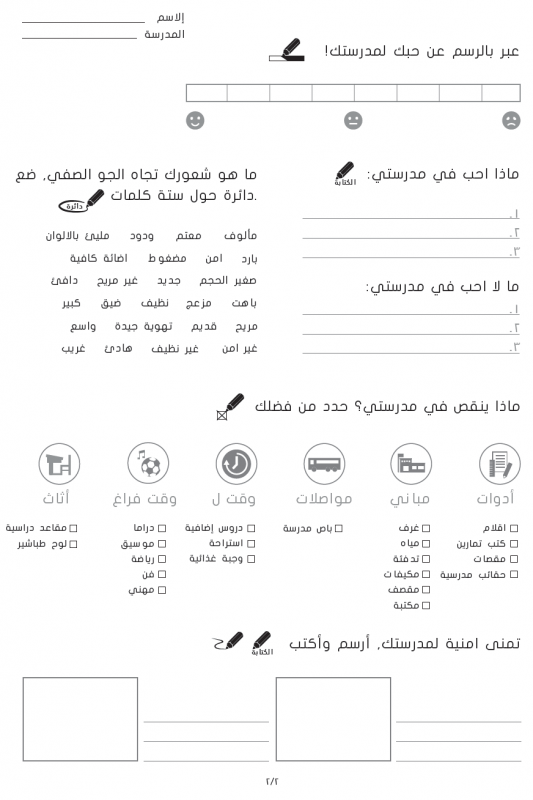

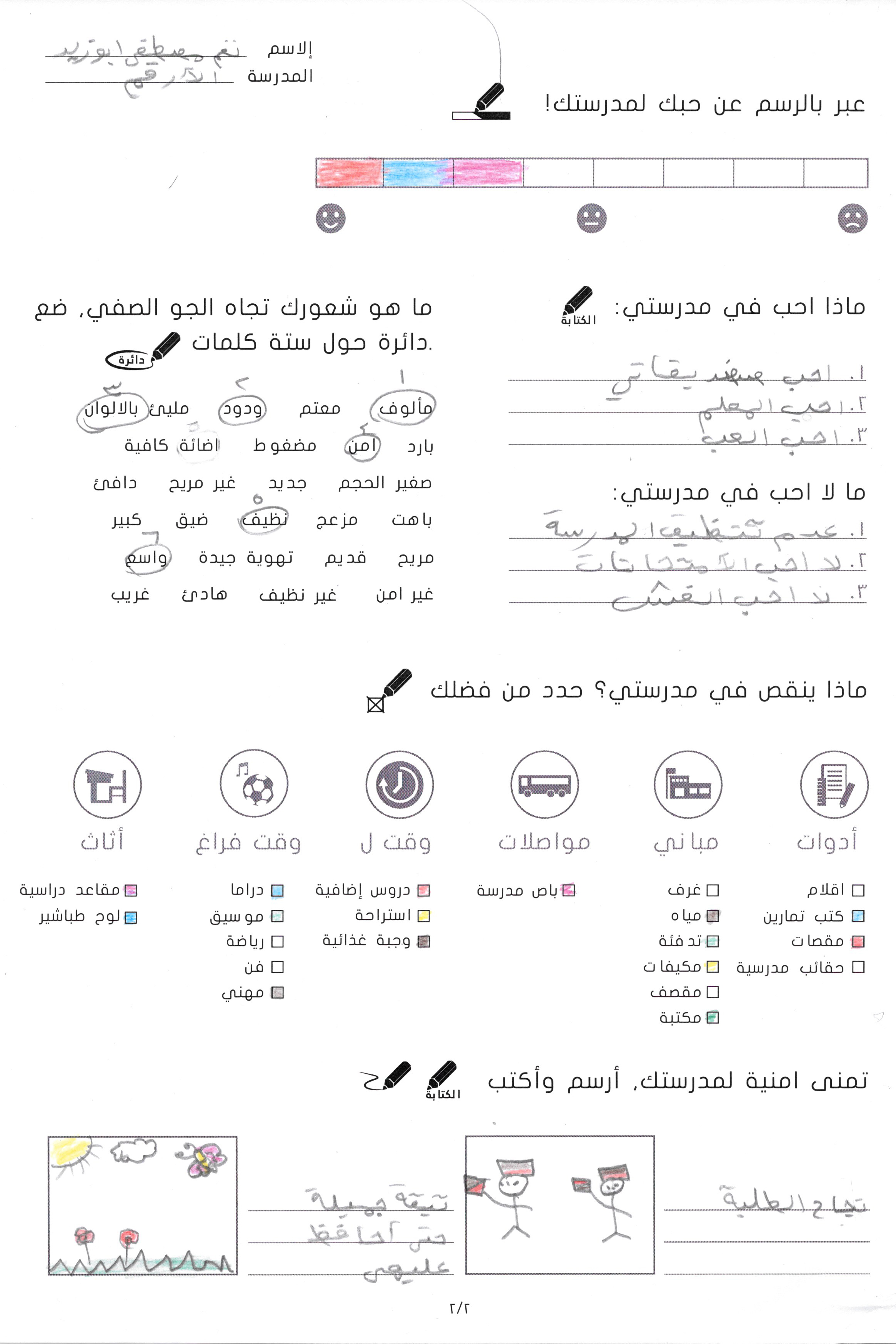

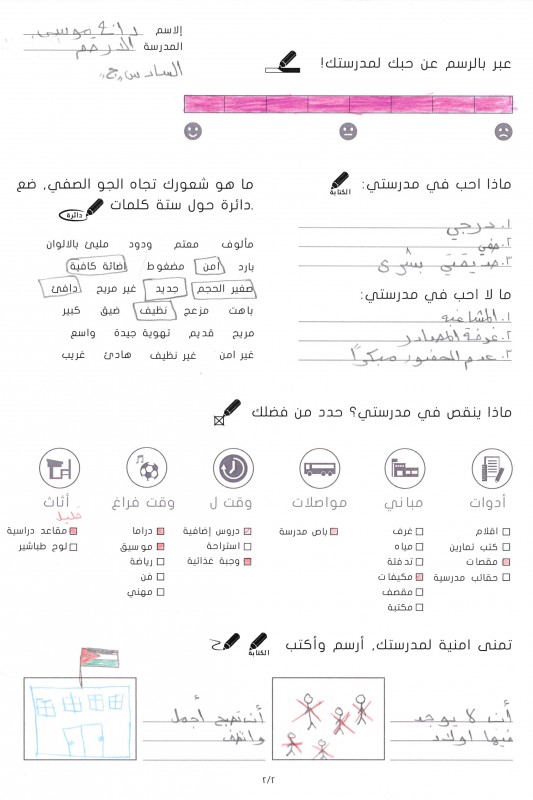

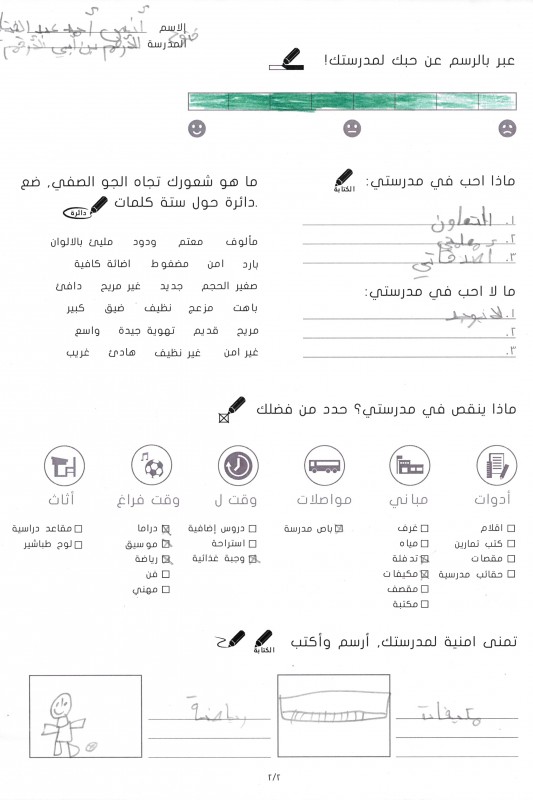

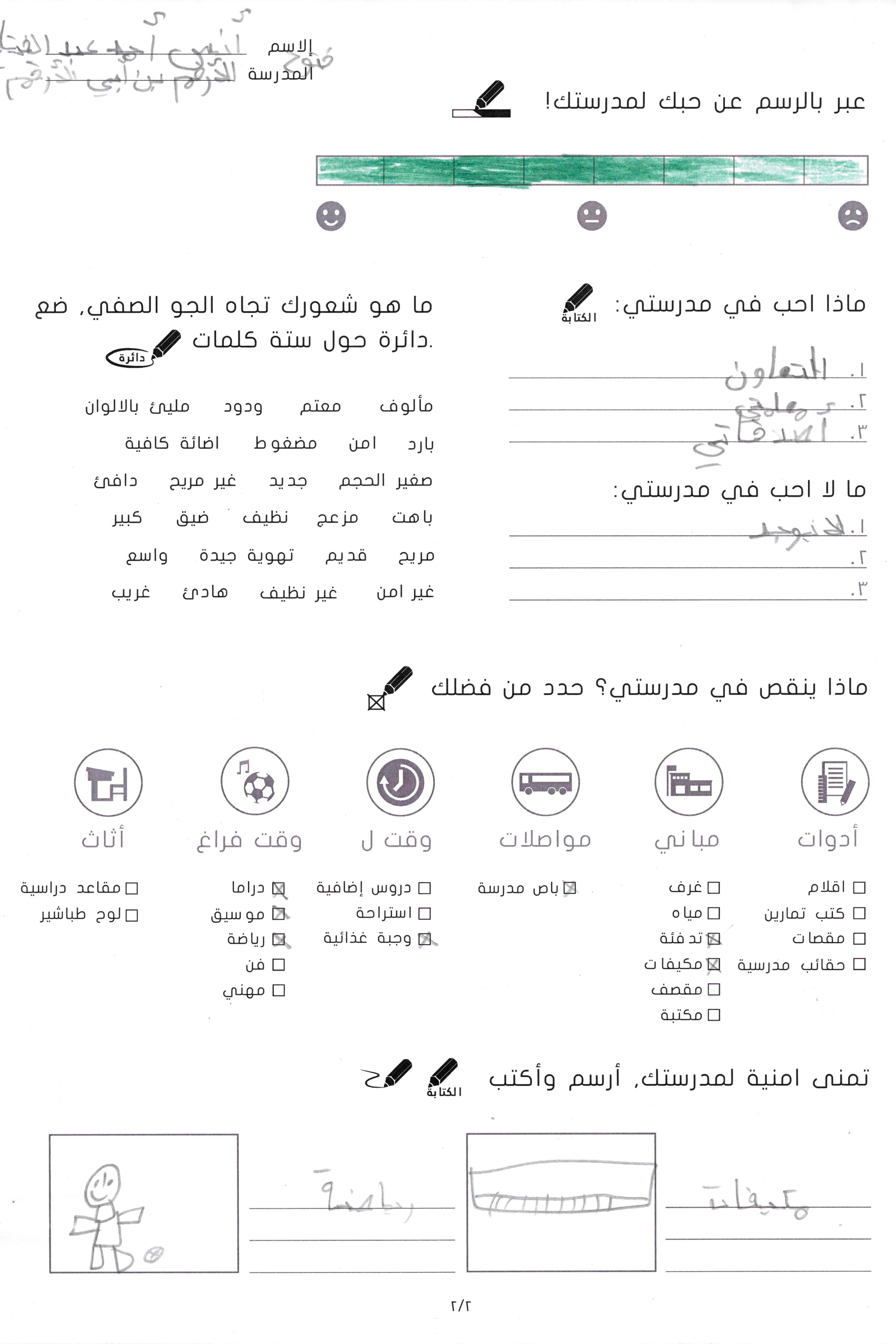

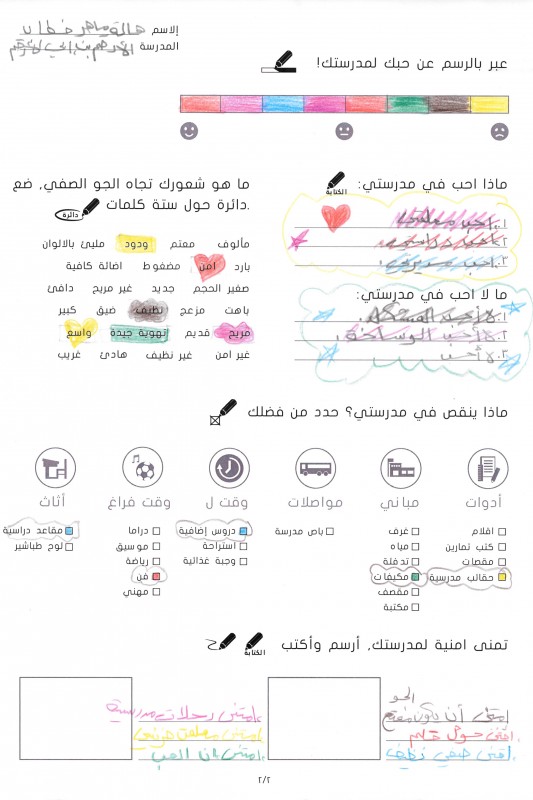

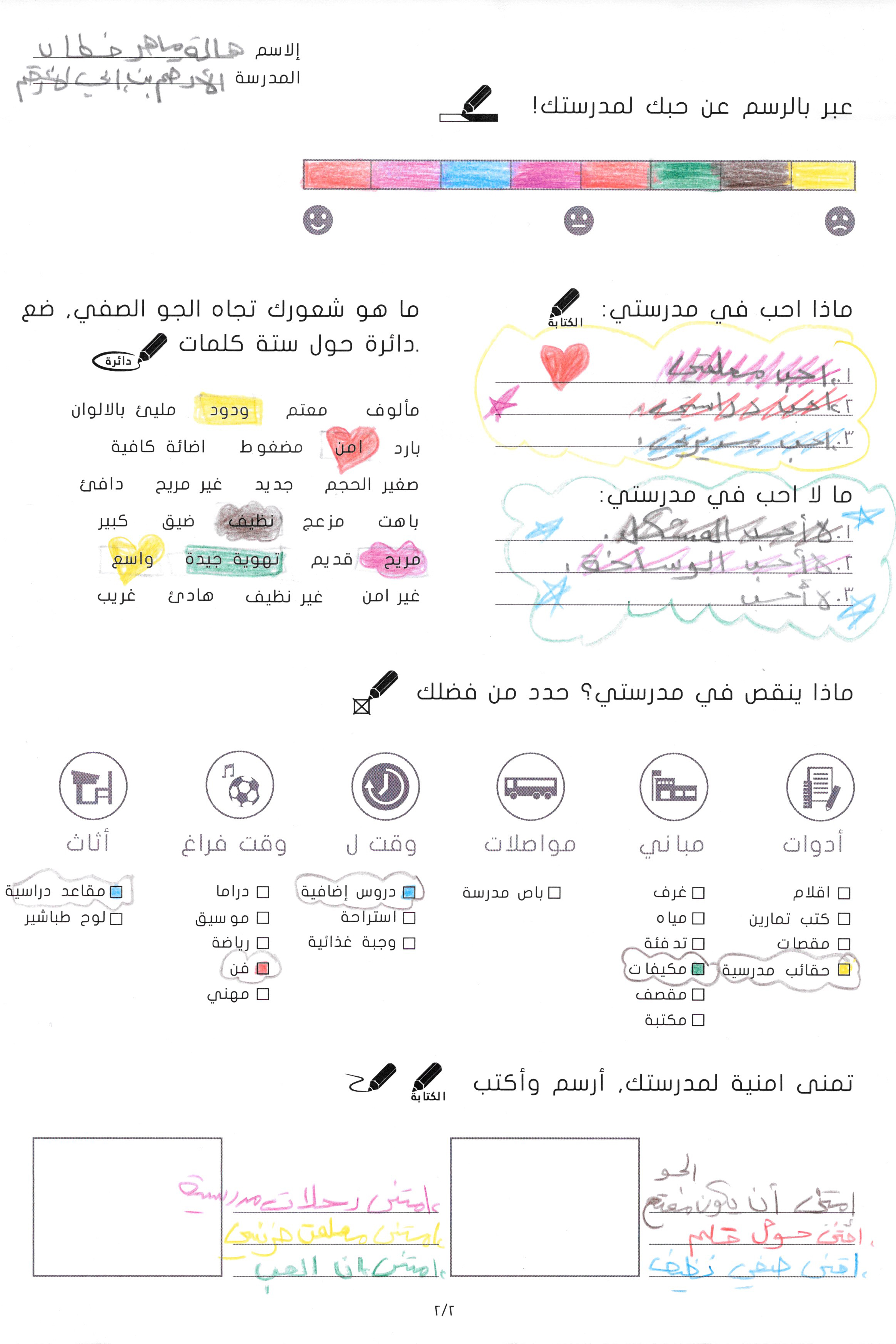

Questionnaire

To obtain a detailed assessment of the school’s situation and to learn more about the children’s feelings and needs, a questionnaire was designed that asks about various aspects of the school’s actual state and its desired state. What kinds of improvements would the students like to see at their school? When directly asked, 90 percent of students report that they like their school very much.*8 on of a scale of 8 More than half of all students describe the atmosphere in their classroom as clean and safe. Negative items such as unsafe, colorless, and strange receive the lowest number of mentions. There are no statistically significant systematic differences between Jordanians and Syrians along these dimensions. In the questionnaire children also had the opportunity to tick items that they would like to have in their school. The most checked items, irrespective of nationality, were air conditioning*77 percent and school bus.*70 percent When asked about what they like about their school, most students mention their friends*70 percent, their teachers*86 percent, and the headmaster*35 percent, who is mentioned by name in many questionnaires. Dirtiness*39 percent is the most frequently mentioned word when it comes to what students don’t like about their school, followed by boys.*30 percent

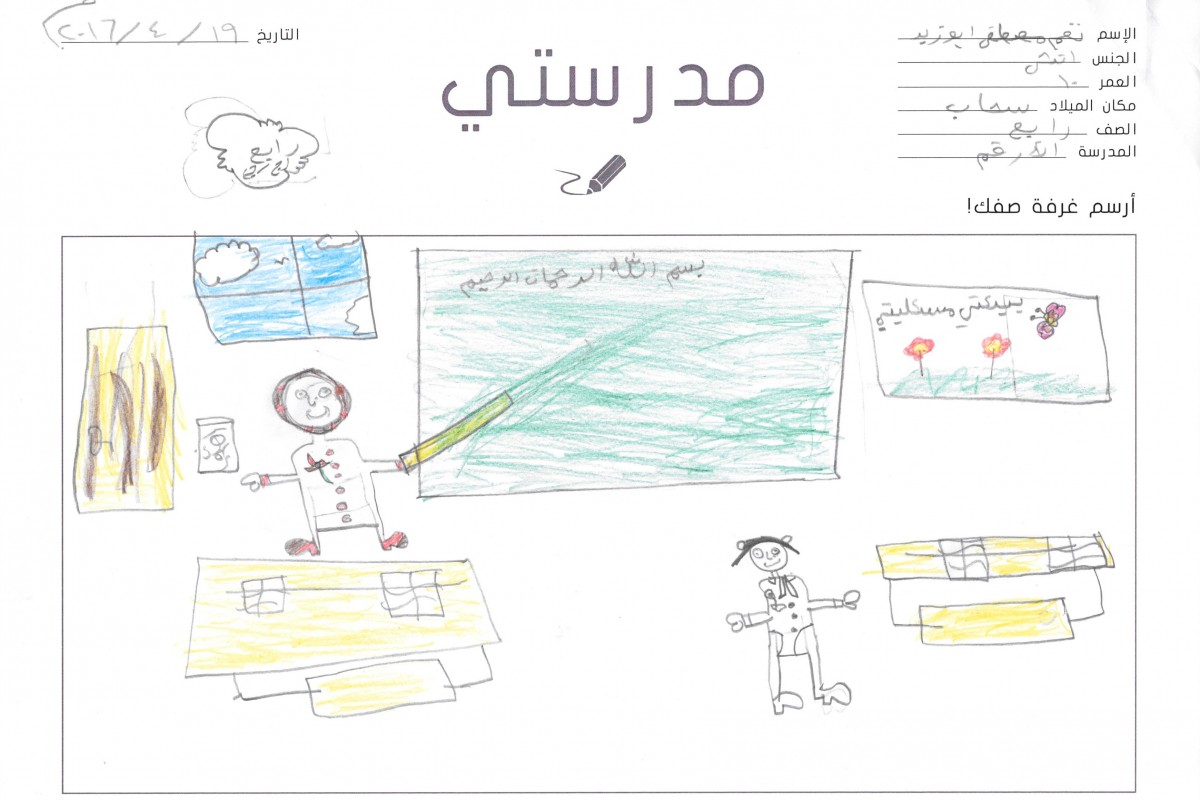

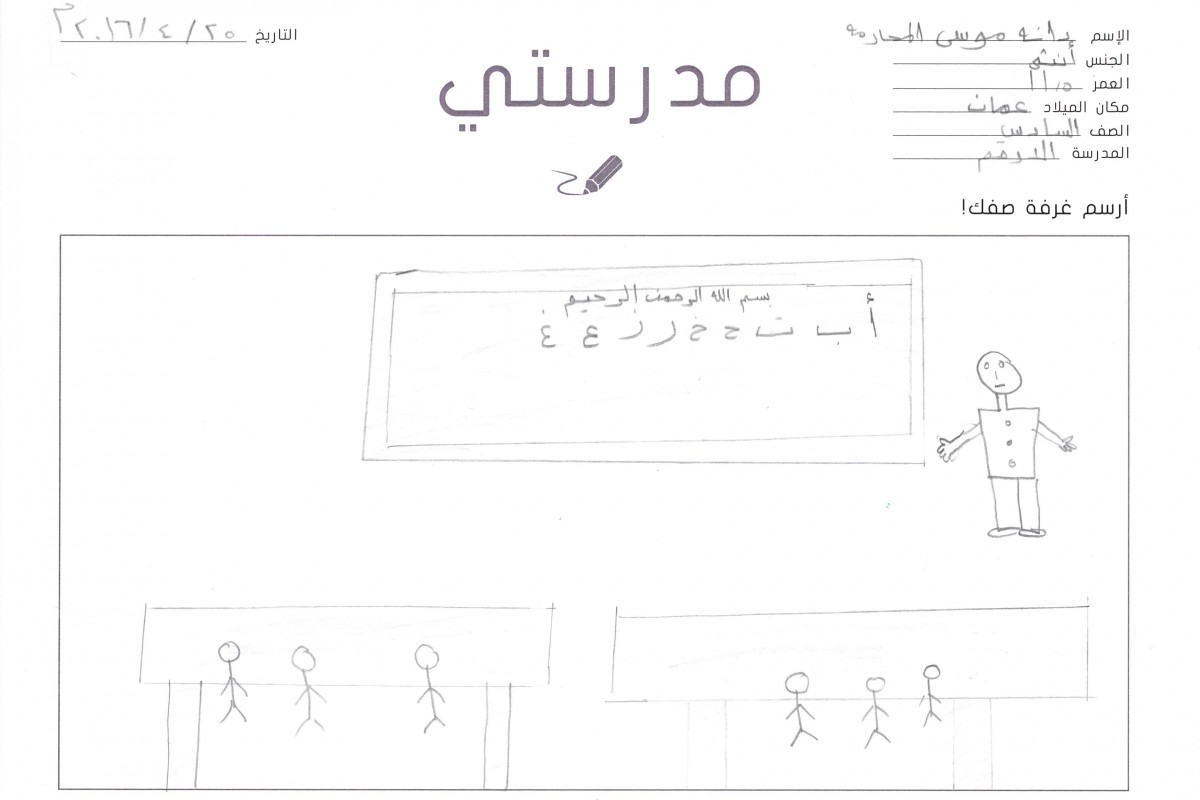

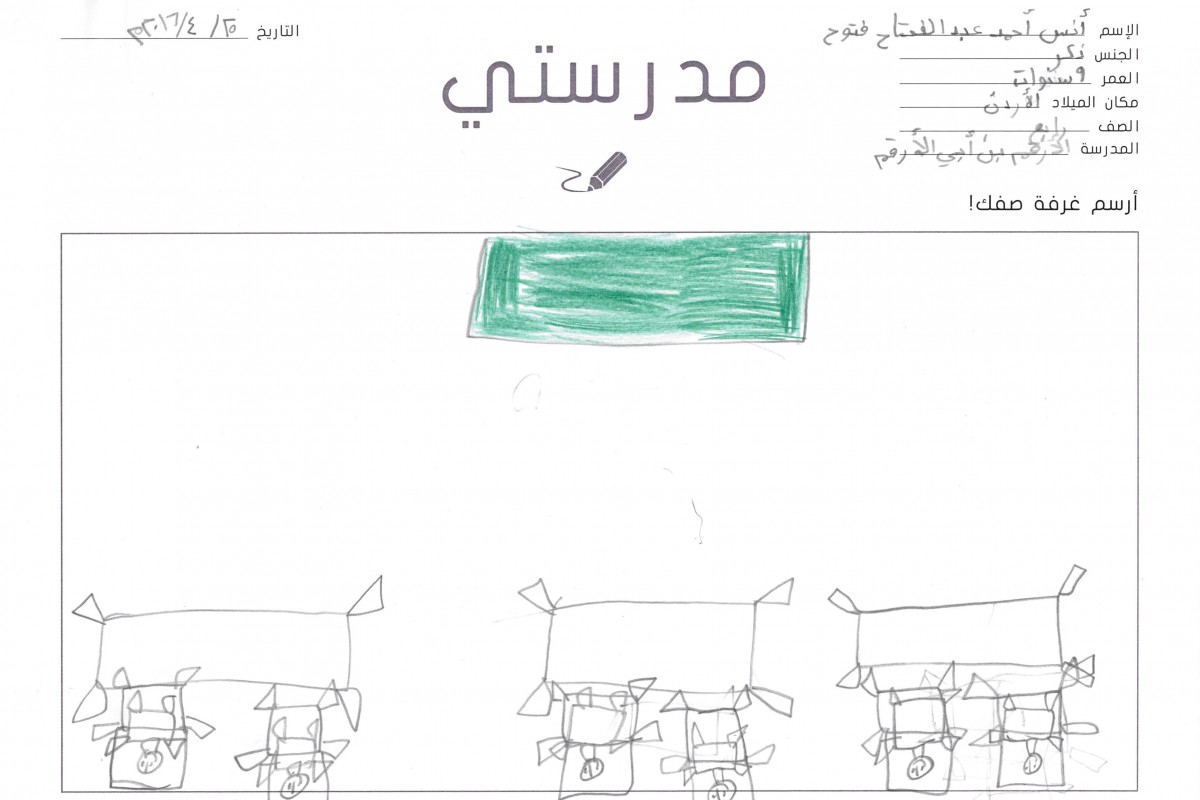

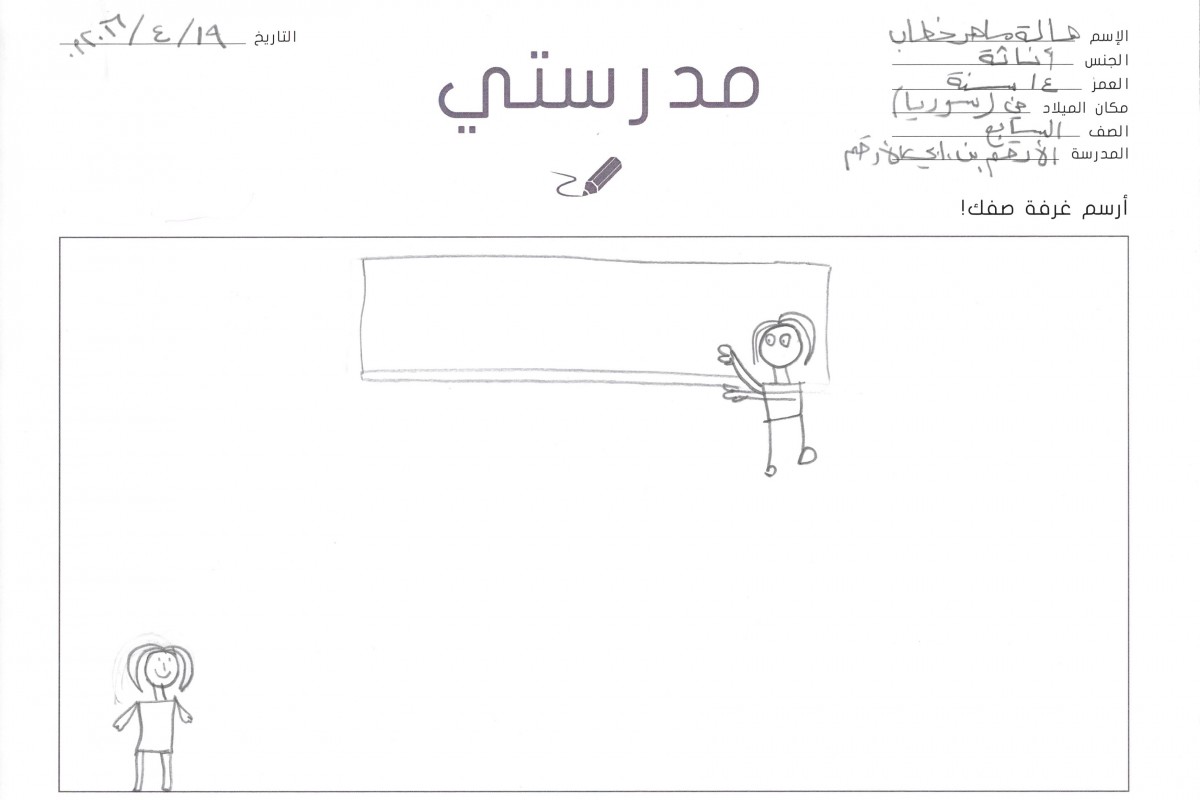

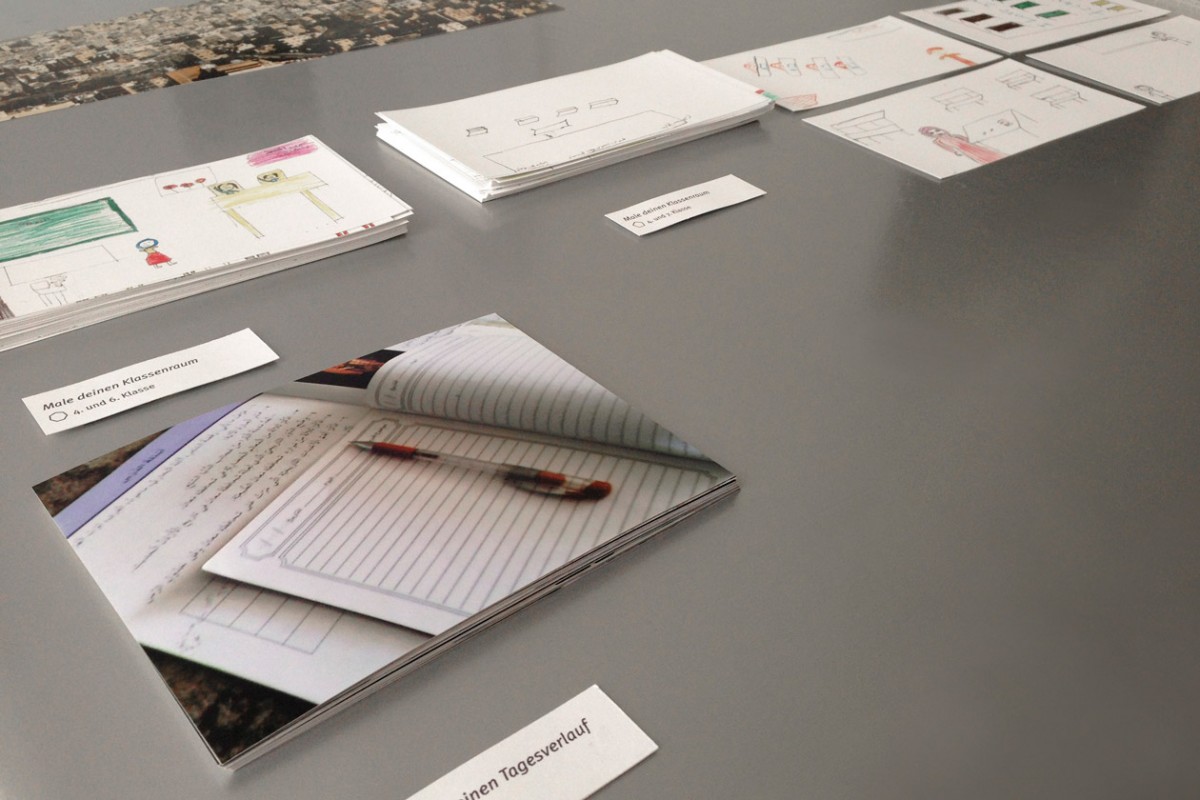

While this shines light onto the objective conditions in the school, the subjective assessment of the students’ situation is of similar interest. The 88 students from 4th, 6th and 7th grade, were asked to draw their classroom. Each student was provided with five colors and one pen.

It becomes clear that Jordanian children use significantly more colors*4.71 vs 2.93, p0.1 (MWU-test)), when drawing their classroom, than Syrians. They also paint in a significantly larger portion of the sheet*2.83 vs 1.52, p0.1 (MWU-test); Student size: 18.09 vs. 20.31, p>0.1 (MWU-test) than their Syrian schoolmates. This continues with the number of teachers and students in the picture.*Teachers: 0.90 vs 0.43, p<0.001 (MWU-test); Students: 2.60 vs 1.1, p<0.001) Conditional on drawing teachers and students, however, there is no significant difference in the size of the figures.*Teacher size: 52.81 vs. 58.75, p>0.1 (MWU-test); Student size: 18.09 vs. 20.31, p>0.1 (MWU-test)

The questionnaire is available in three languages. The first drafts are in German. The final version of the questionnaire was translated into English to share it with the project partners in Jordan. Finally, it was translated into Arabic for the children with the help of Madrasati. In Jordan, it was given to the students of the double-shift school Al-Arqam. The school library was used as a place for students to complete the questionnaire. Each student received five color pens and a pencil to ensure identical conditions for all respondents. Overall, 88 questionnaires were completed by Syrian and Jordanian students in fourth, sixth, and seventh grade.

Impressions of the Filling out of the questionnaire

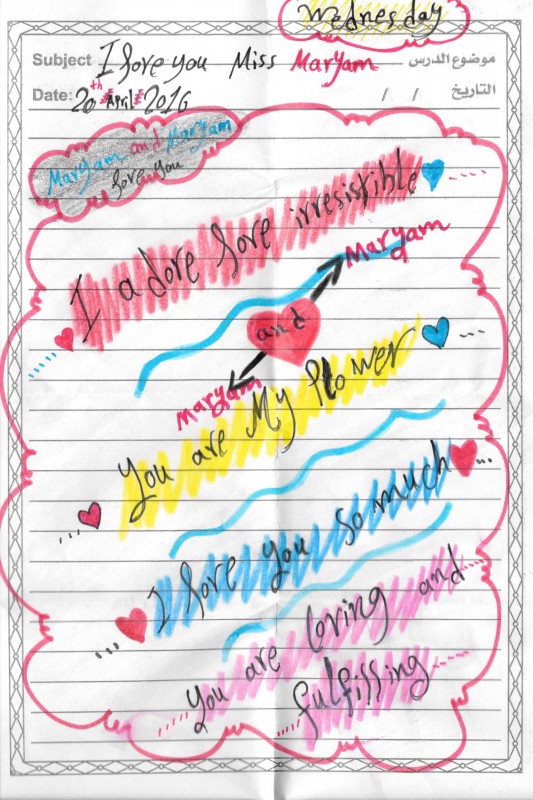

Cultural Probe

Developed in the late 1990s, cultural probe is a complex qualitative method in the field of design. It provides personal, intimate, and detailed access to people’s desires, opinions, and aesthetic and cultural preferences. A cultural probe is a kind of observational study, aiming to provide deeper insights into people’s lives. Selected actors are given small packages that can include all sorts of objects (e.g., single-use cameras, audio recording devices, postcards, or diaries), and they are asked to use these media in certain situations or intervals over a certain period of time (one or more weeks). Depending on the research question, cultural probes can be designed in different ways. In “Double Shift” the cultural probe was kept very simple, not least because of the language barrier. For organizational and stylistic reasons, small digital cameras were used, which are suitable for children.

These cameras were given to selected students, who were asked to take pictures of their school and to document their daily routine. The cultural probe technique provides personal and visual insights into student’s daily experience – insights, which otherwise would remain hidden. How do they live? How do they get to school? What do they eat? Who are their friends? Do they have any brothers and sisters?

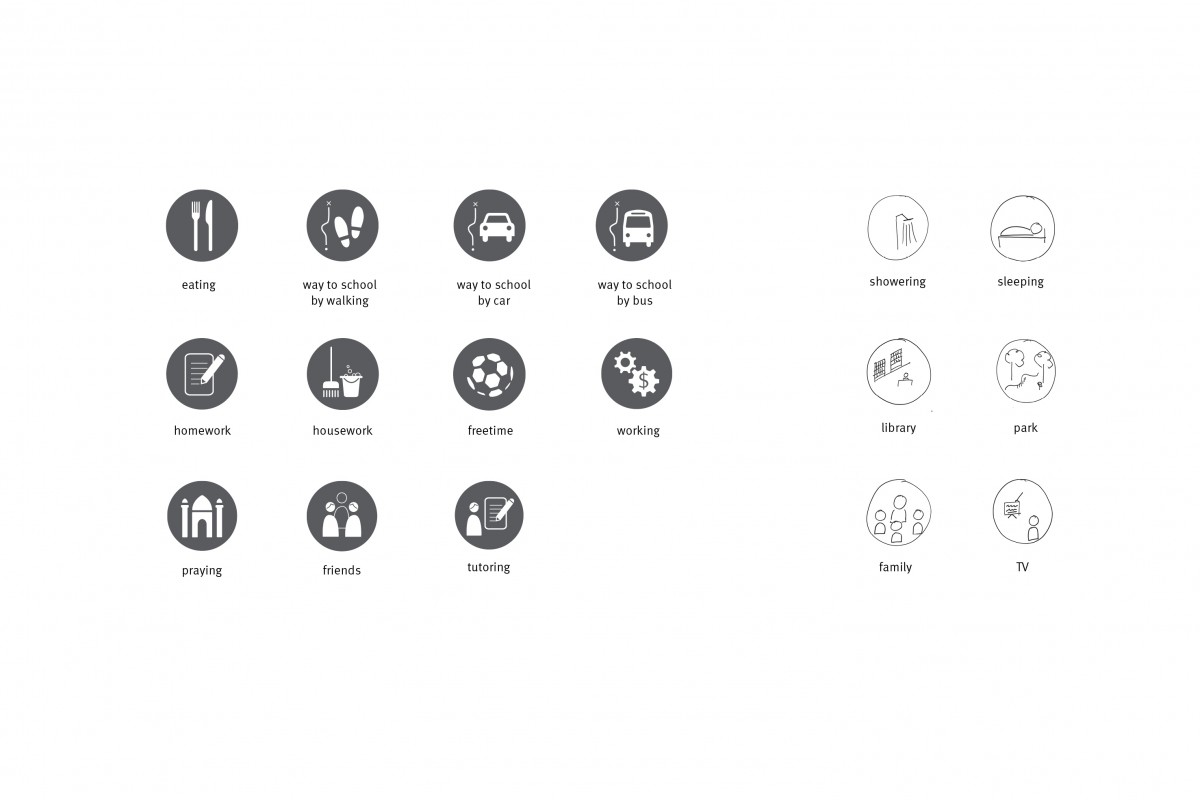

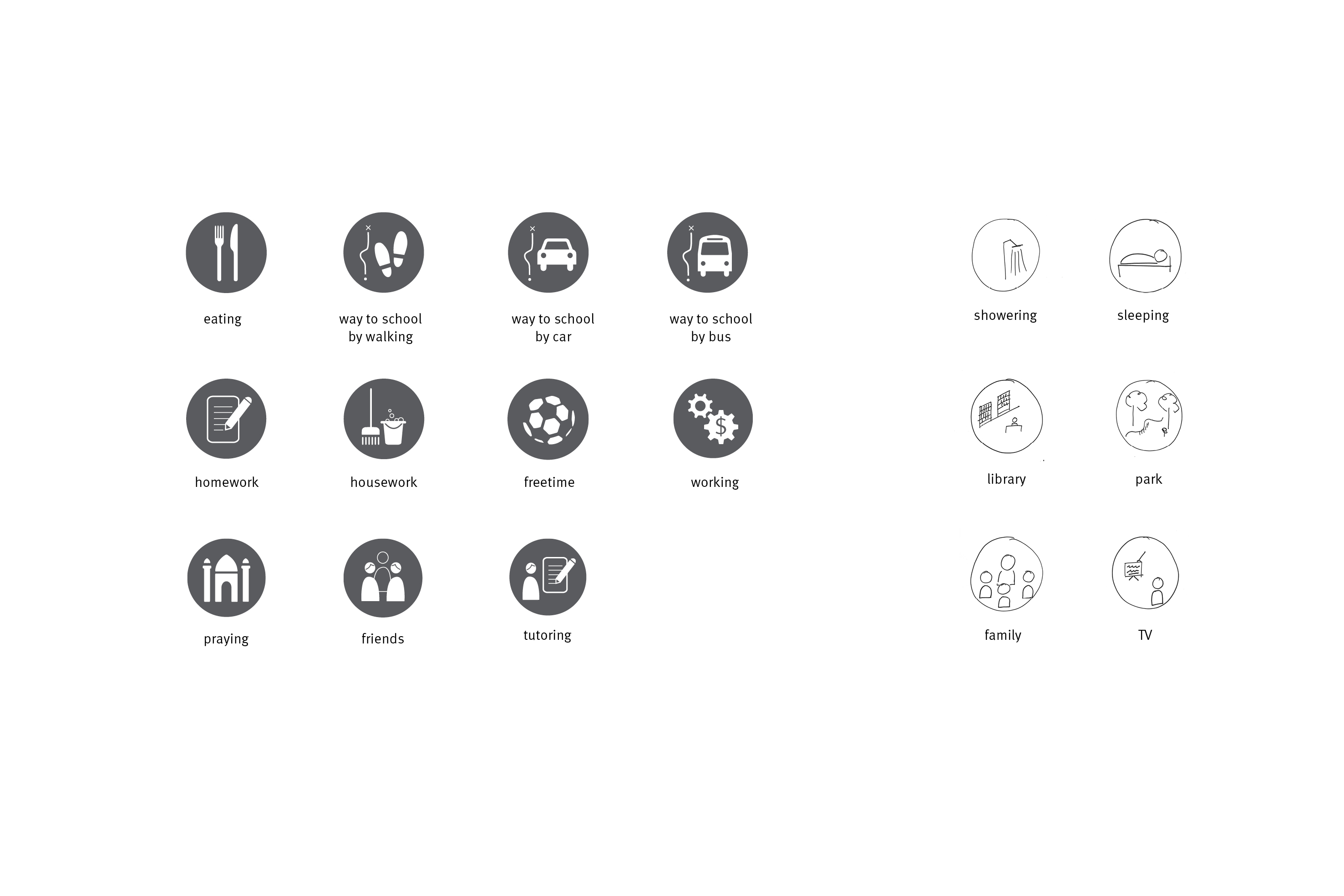

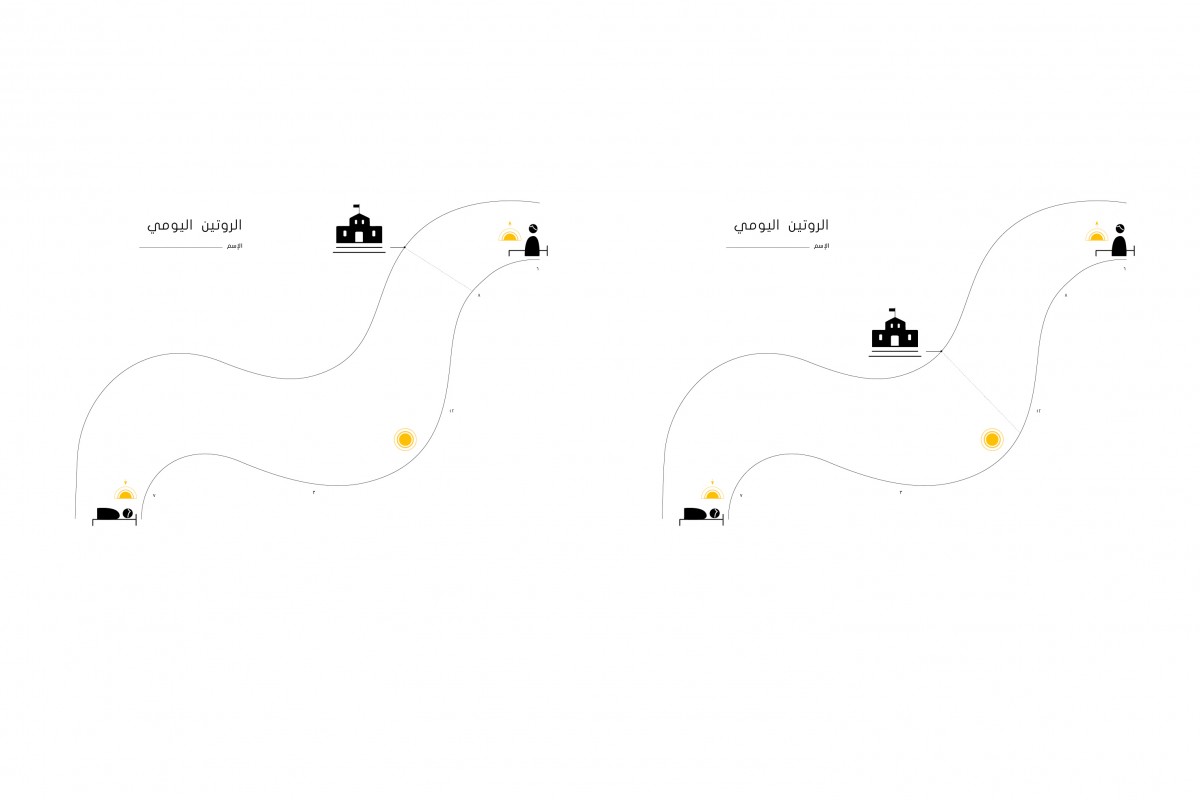

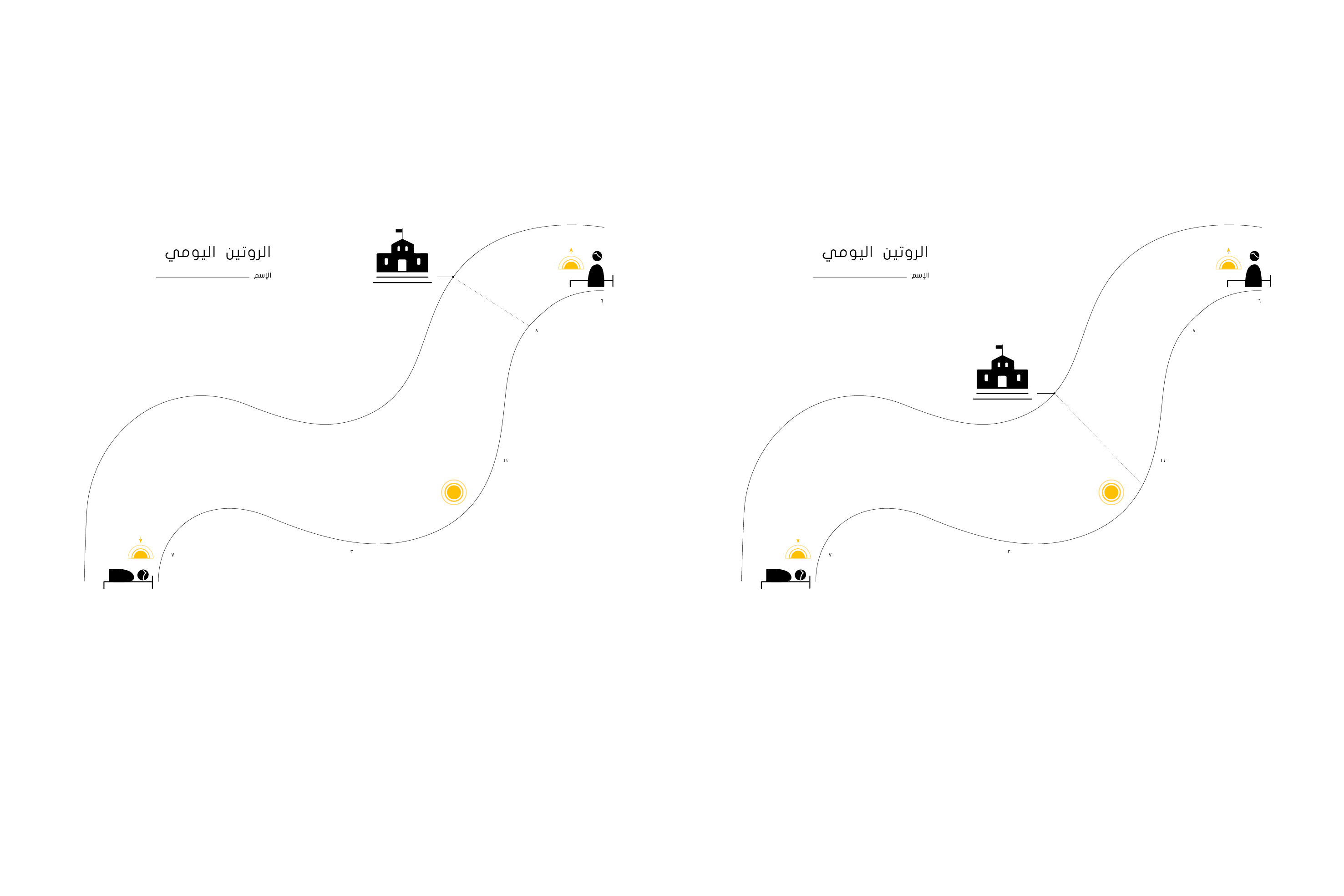

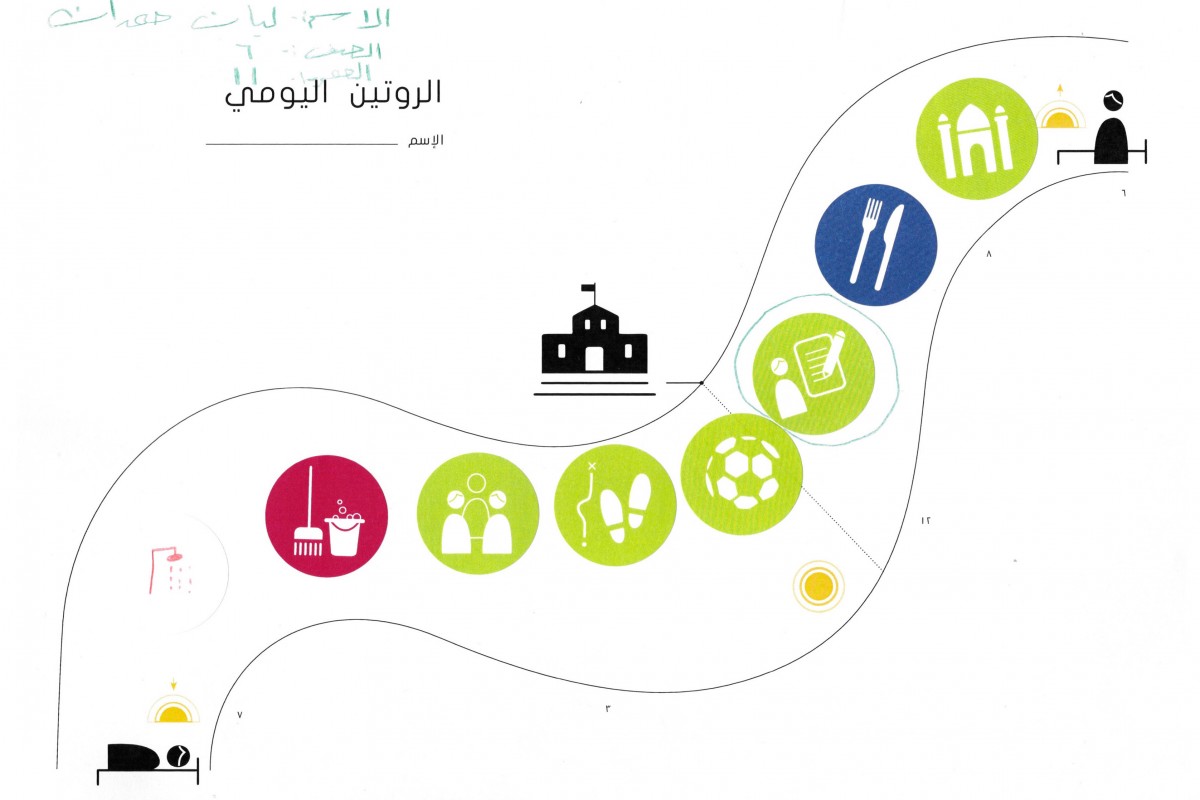

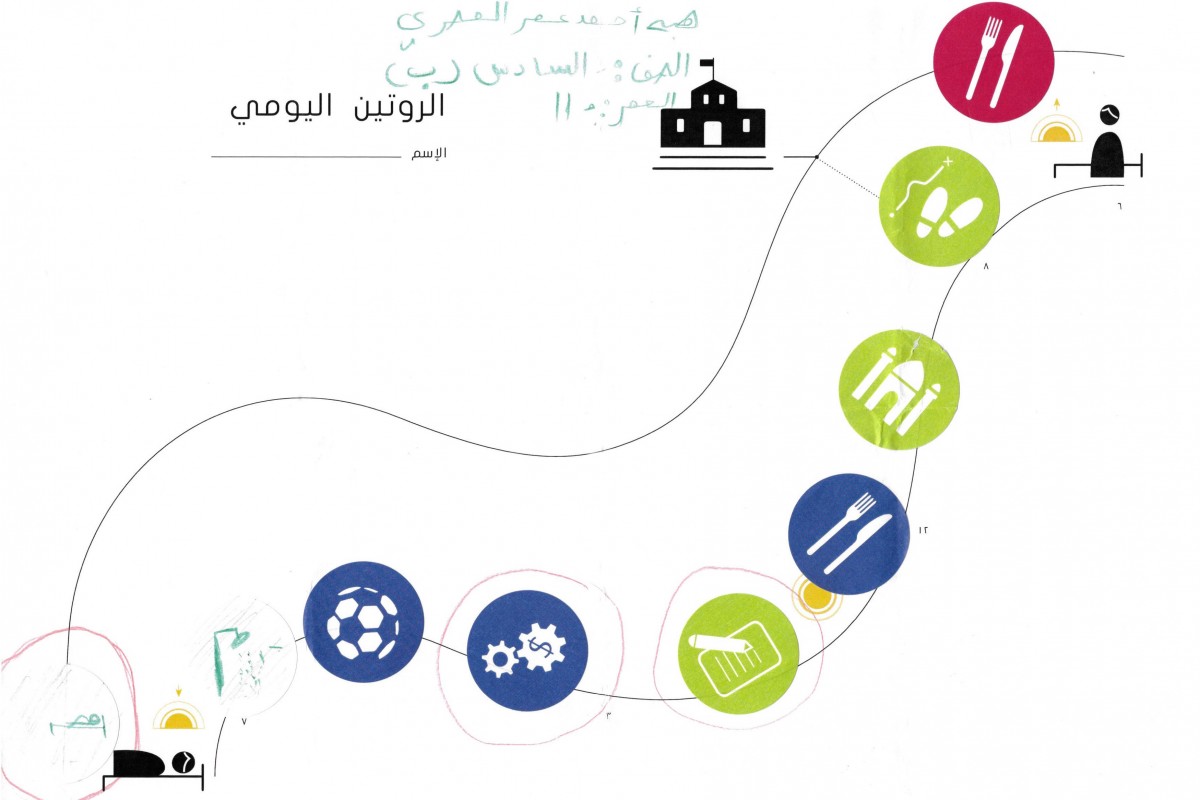

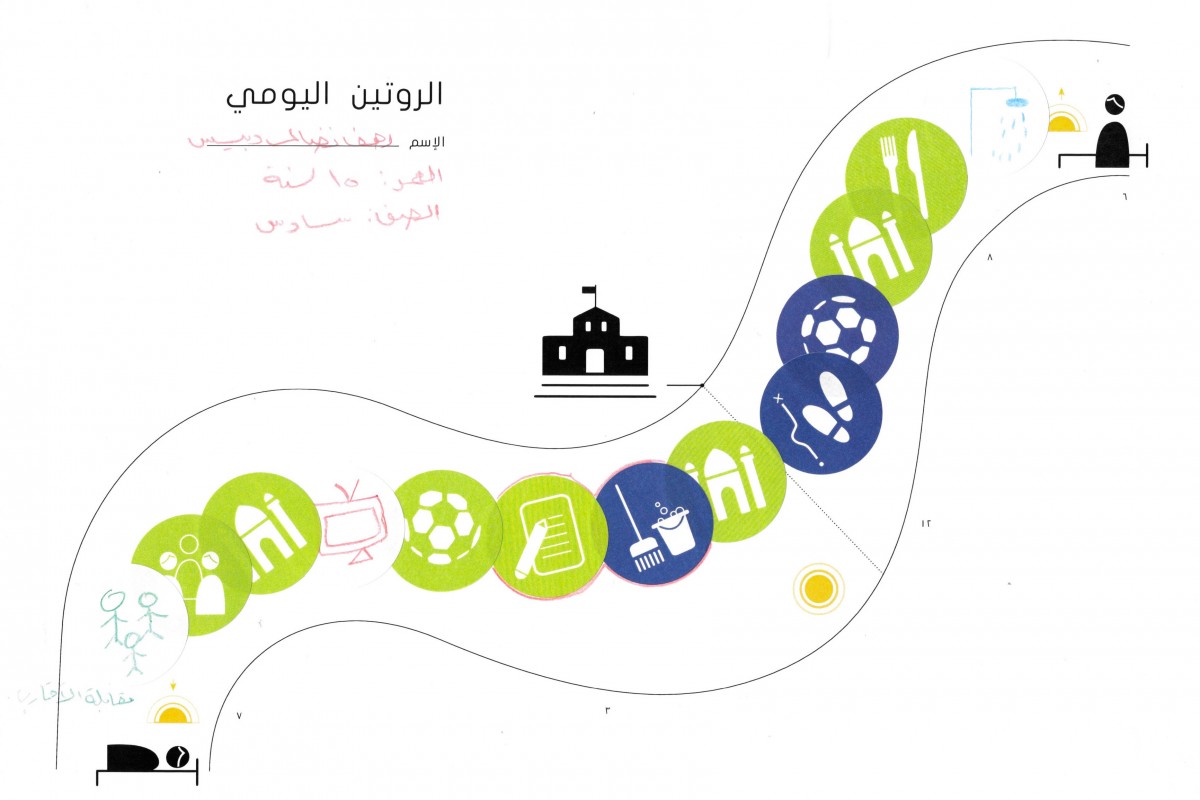

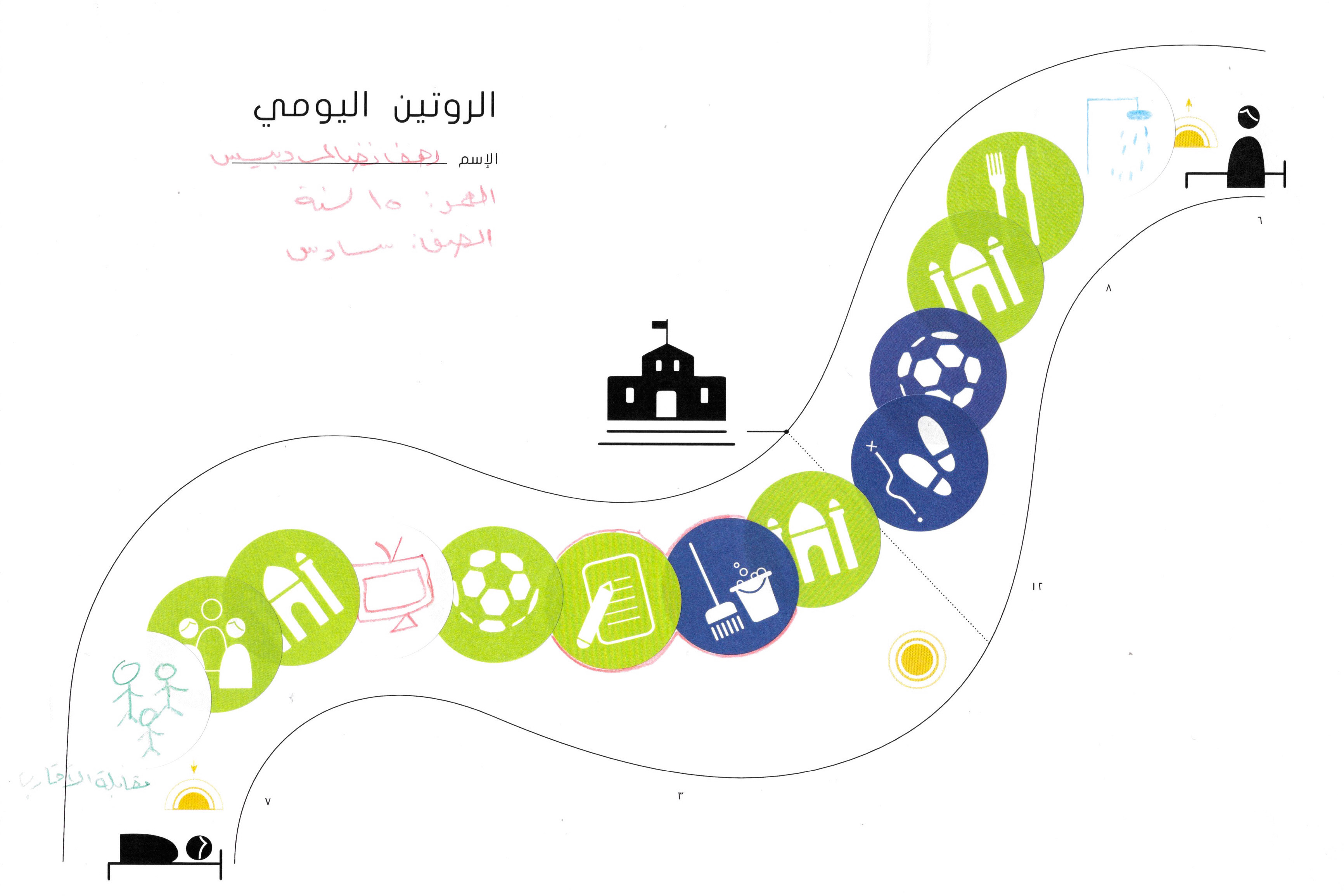

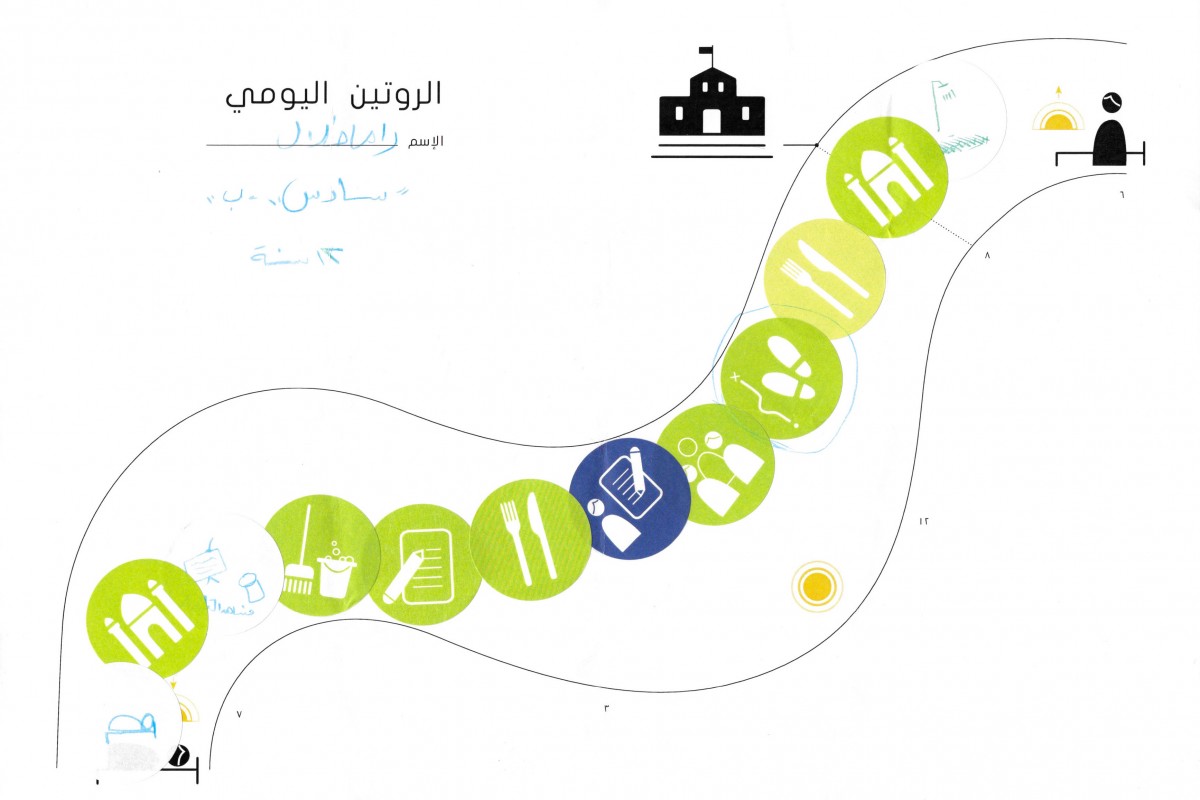

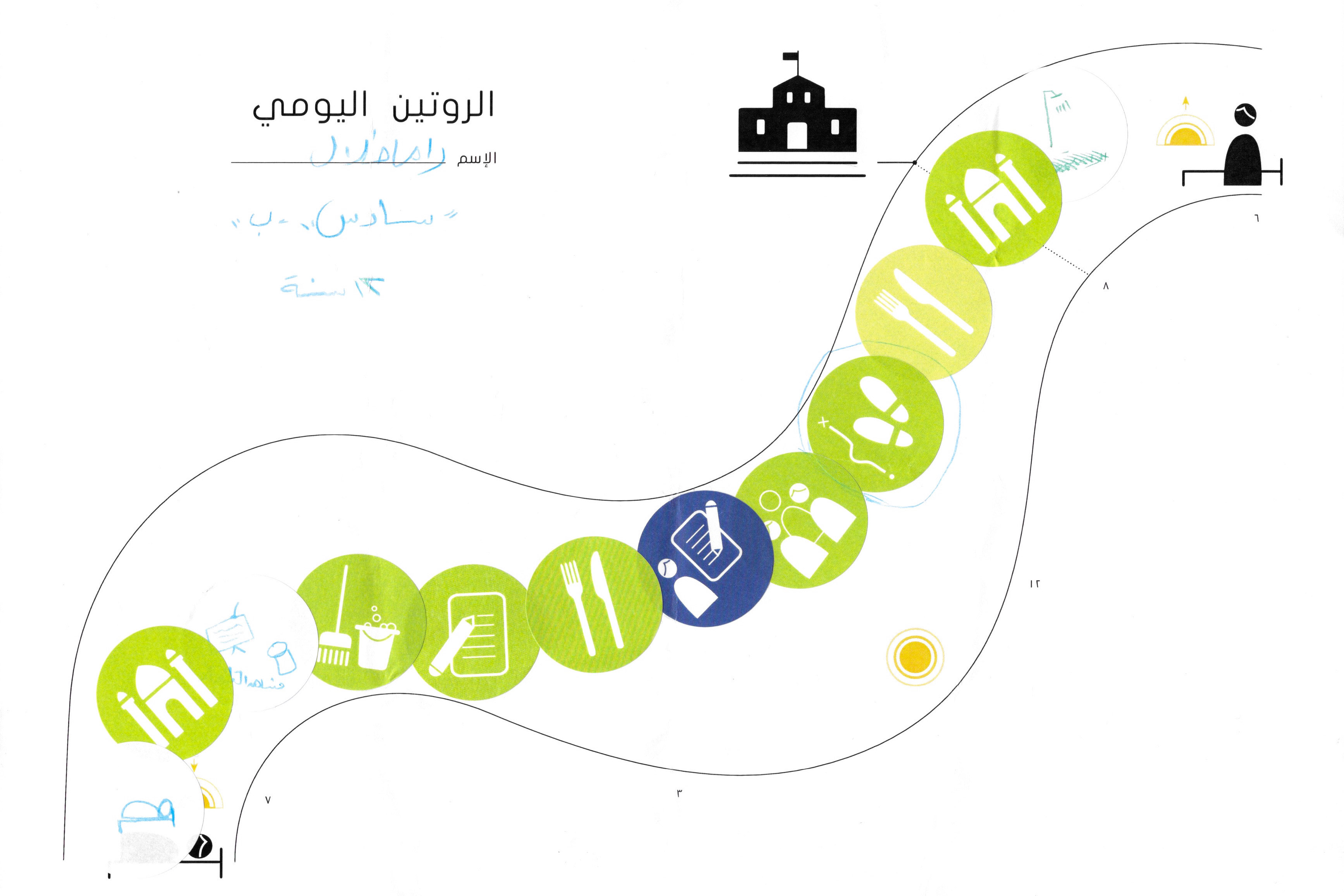

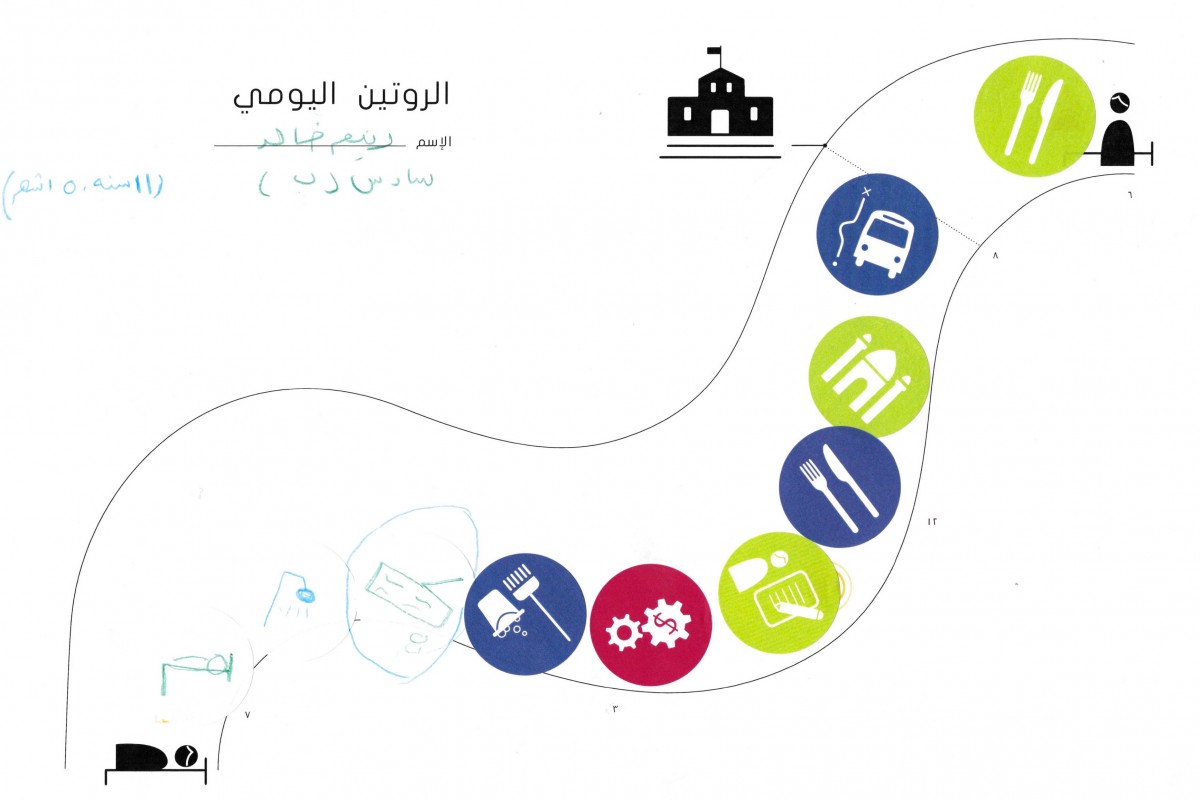

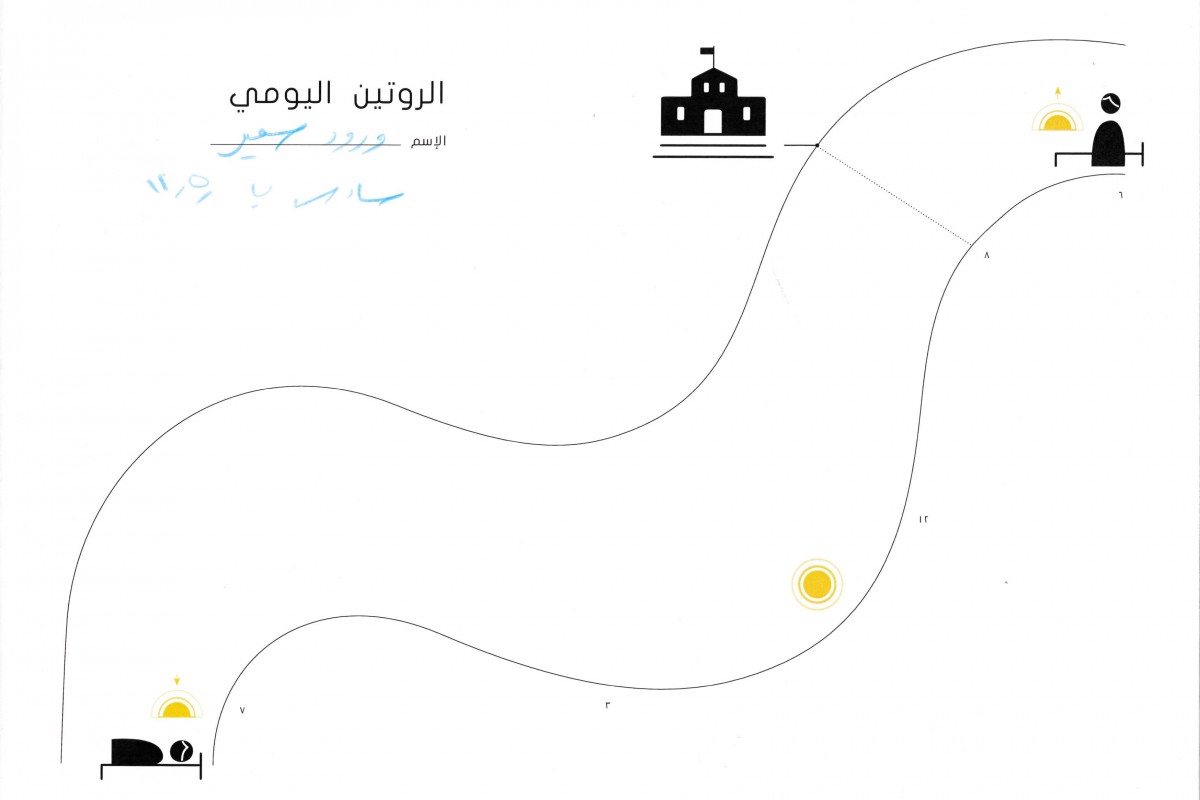

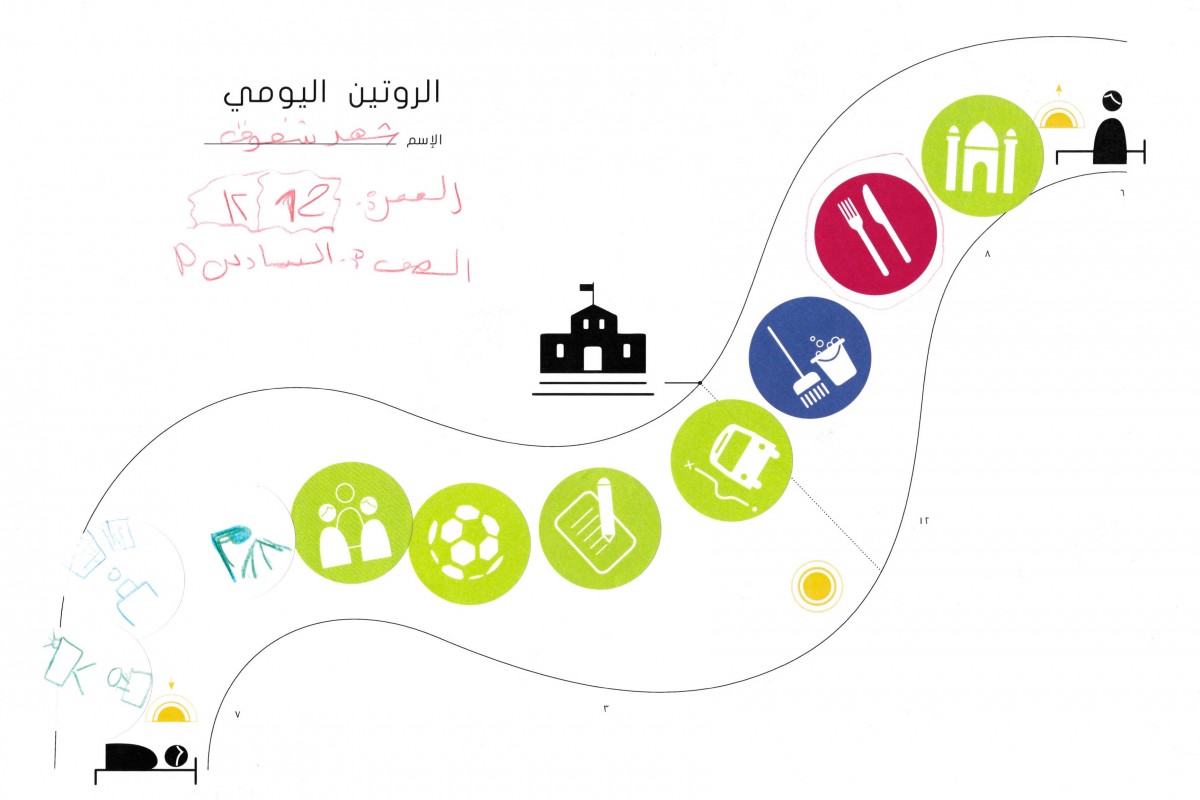

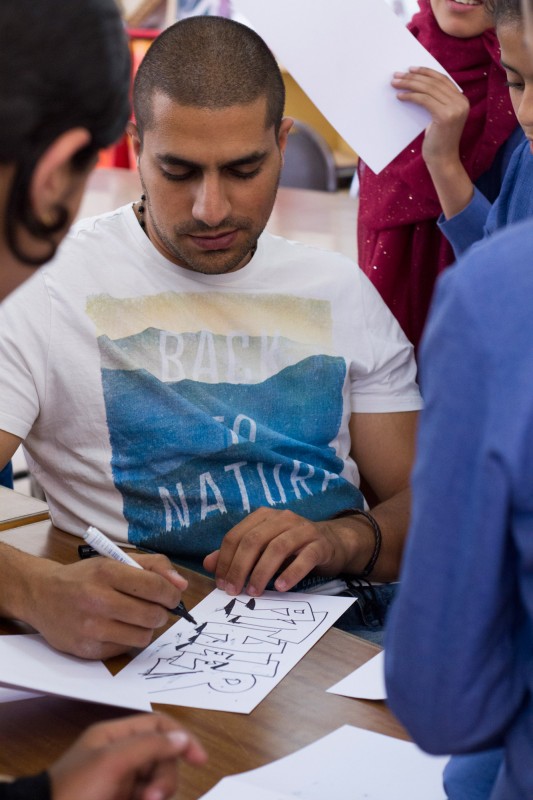

Workshop

Based on the first field trip, ideas for a participatory workshop were developed to learn more about students’ daily routine. To bypass the language barrier, visual devices were used as often as possible. For each daily activity, a pictogram was designed. The decision which activities to select for the pictograms was based on the analysis of the conversations and observations during the first field trip. For organizational reasons, the entire workshop was prepared in Berlin, including the printed materials. The pictograms were printed as stickers, each in three different colors. The colors enable the children to rate their daily activities – whether an activity is a lot of fun, some fun, or no fun at all.

Impressions of the Workshop

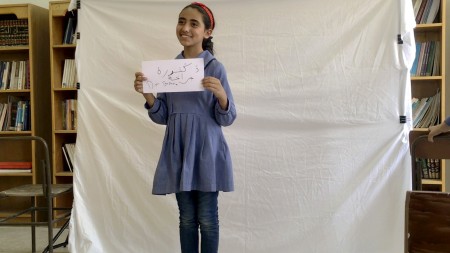

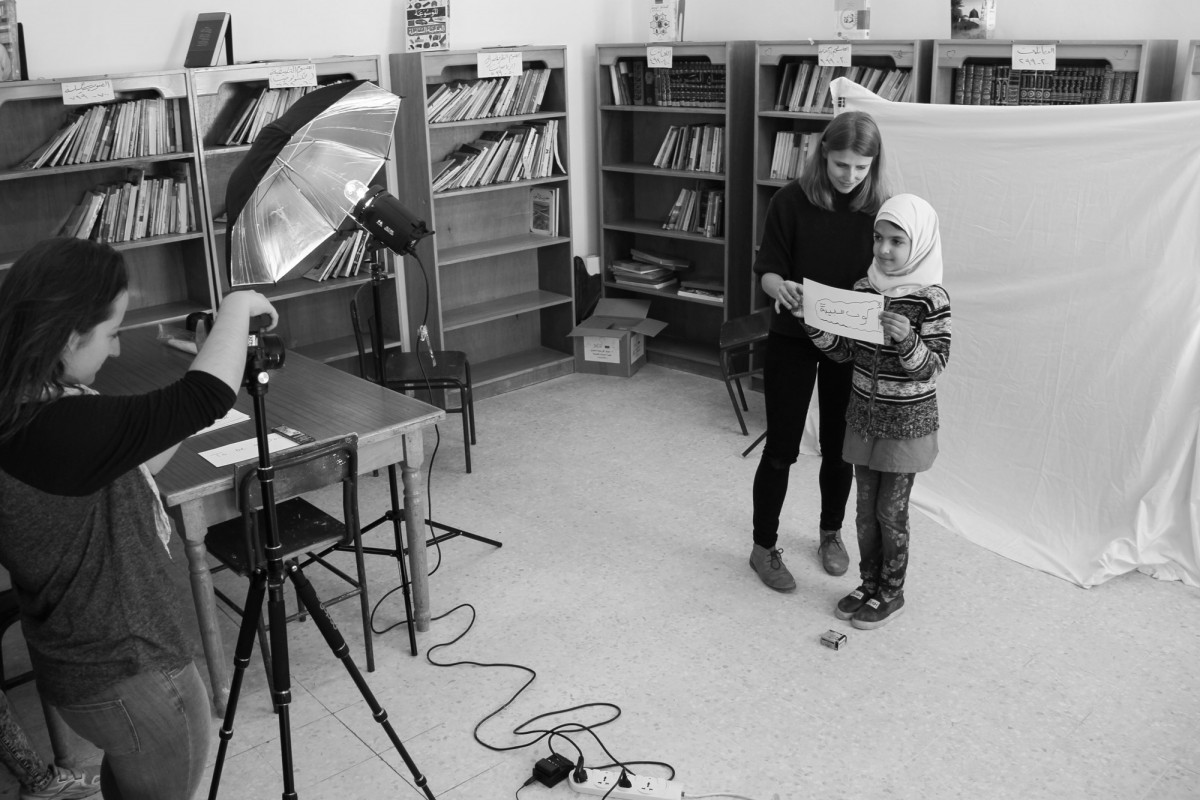

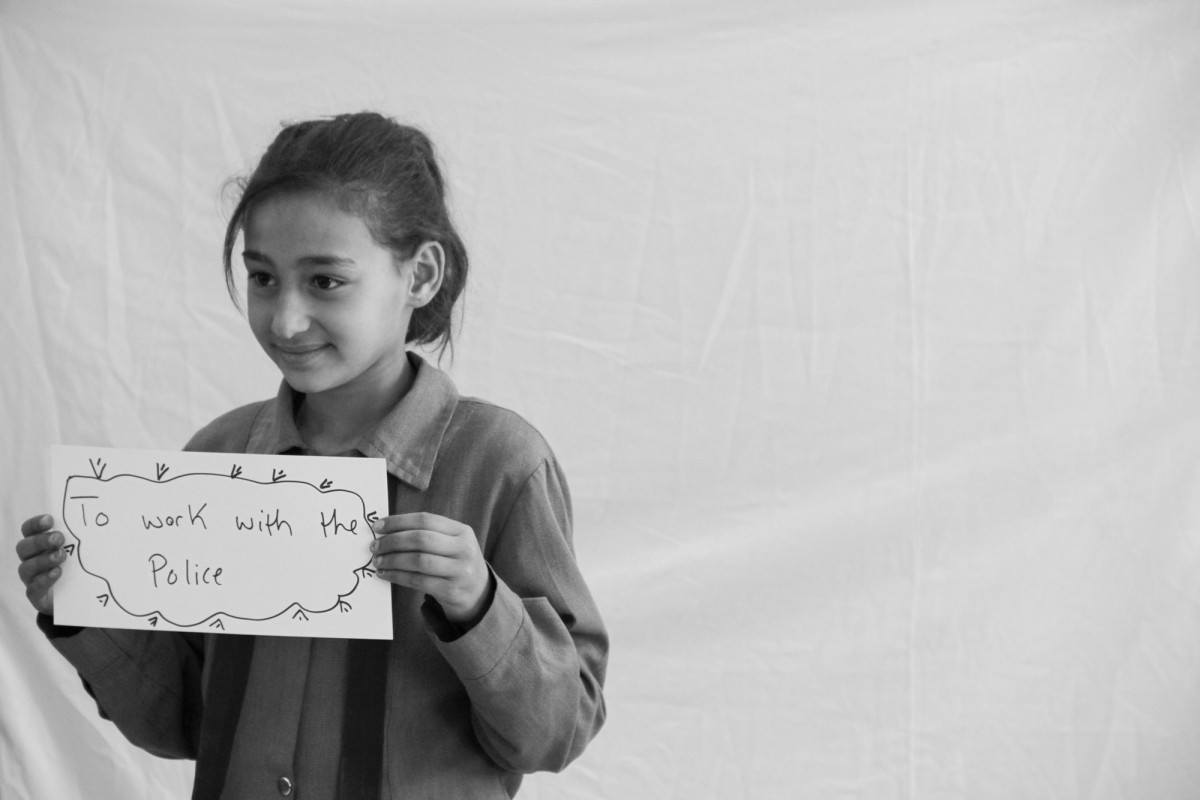

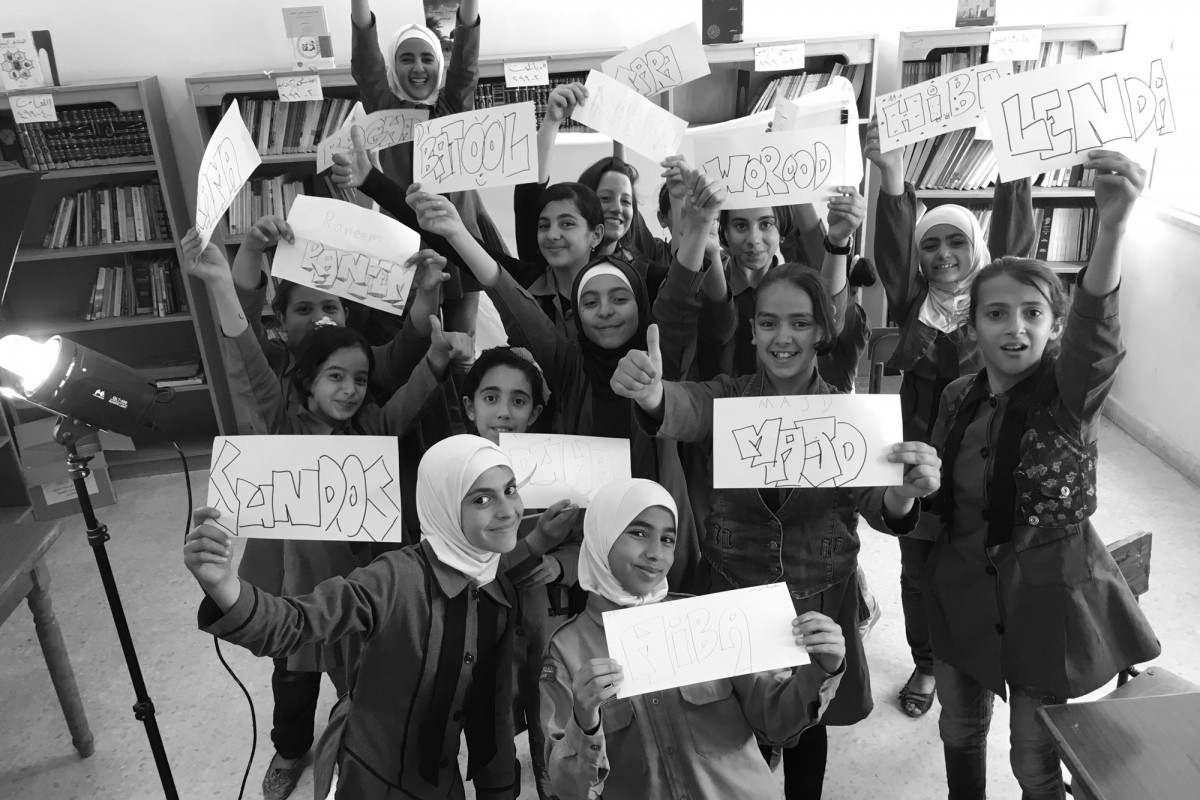

Portraits

“We also took portraits of the students at Al-Arqam. Students are portrayed holding their wishes handwritten onto a sign. Overall, we took pictures of 85 children: the same Jordanian and Syrian fourth, sixth, and seventh graders who also filled in the questionnaire. In fact, for reasons of time and logistics, the photo shooting took place in the school library right after students completed the questionnaire. The shooting followed a precise procedure: The students write down their wishes in Arabic; Jameel from Madrasati translates them into English. Those who are done are photographed one after the other. Although they have to wait in line for this, the children are very patient.

Nearly all students wish they will have jobs when they’re grown. Many aspire to prestigious positions, such as becoming a doctor. *28 of 85 students Becoming a teacher is also quite popular. *16 of 85 students Other professions the children wish to learn are engineer *8 of 85 students and lawyer. *5 of 85 students From among the seventh graders of the afternoon shift, seven Syrian girls wish they could leave Jordan, either to return to Syria, emigrate to Germany, or move somewhere far away.”

Marjam and Paula // Designers, team members of “Double Shift”

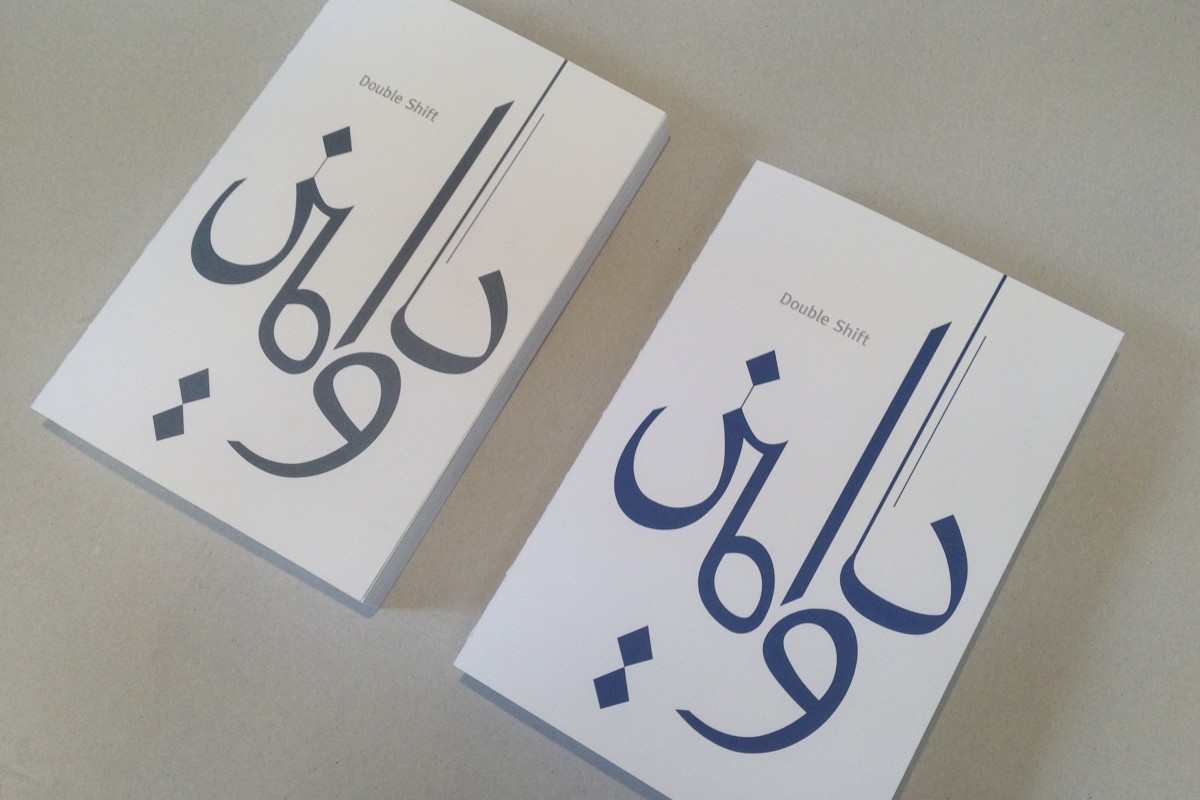

Exhibition and Book

The project report of “Double Shift” was published in German and English. It provides detailed information about the course of the project, featuring photos taken during the field trips, draft designs and project plans, as well as research results and the design of the website.

The book and research results were presented within the annual exhibition of the Berlin University of Art in summer 2016 – an “informational journey” through the current situation of public schooling in Jordan.

Sources of the website’s content

- UNHCR, Syria Regional Refugee Response Data Portal

- UNHCR

- Around 37 percent are under 15, Annual Report 2014

- Impact of Syria Crisis on education in Jordan (2015-16)

- In addition to public schools there is a big well-run private school sector.

- 60 percent (Impact of Syria Crisis on education in Jordan (2015-16))

- UNHCR 2017

- 143,259 children enrolled into formal education (Impact of Syria Crisis on education in Jordan (2015-16))

- 88 students were asked to draw their classroom. Each student was provided with five colors and one pen. It becomes clear that Jordanian children use significantly more colors than Syrians, when drawing their classroom. They also paint in a significantly larger portion of the sheet than their Syrian schoolmates. This continues with the number of teachers and students in the picture.